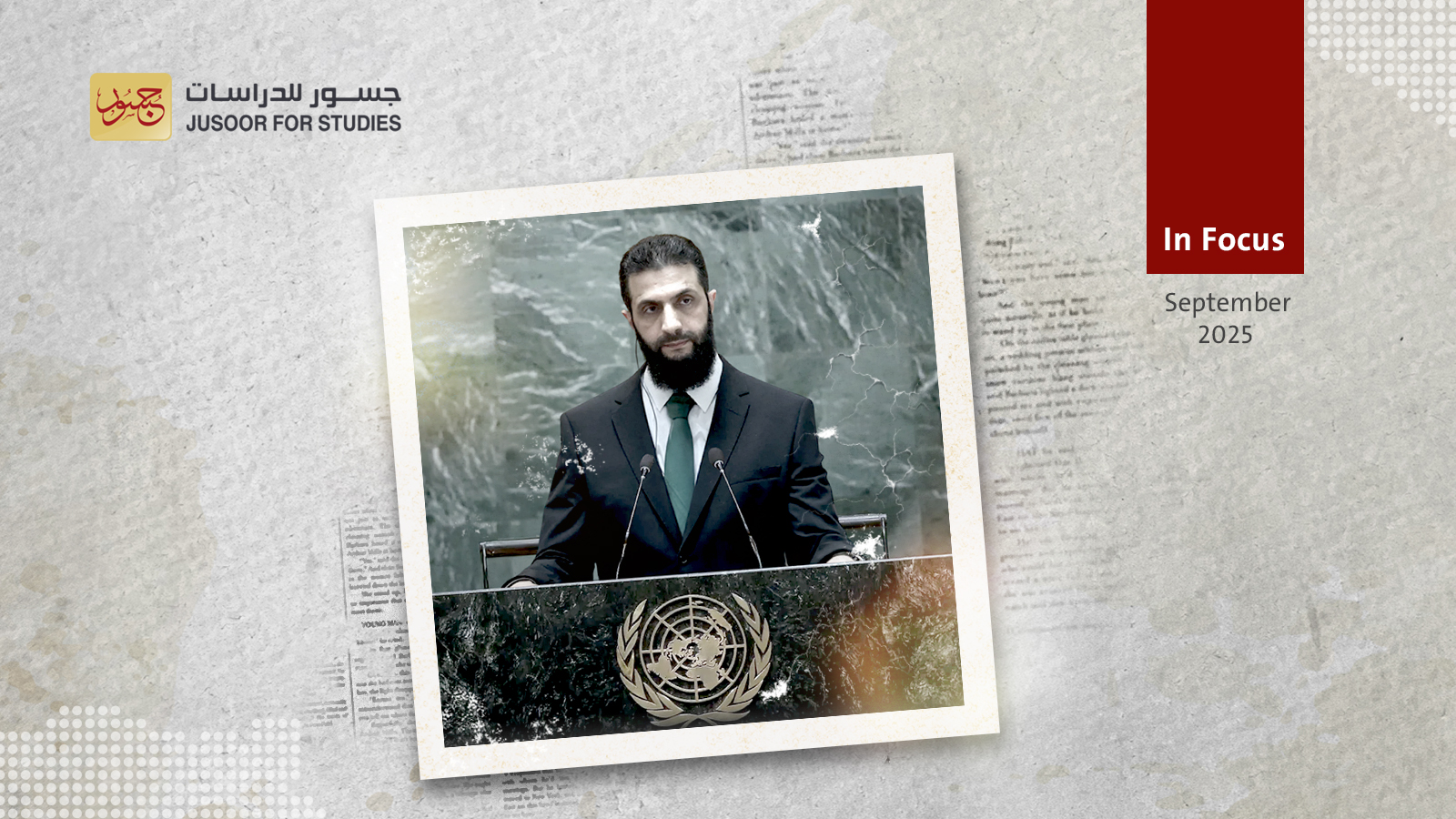

The Impacts of Al-Sharaa’s Historic UN Address

Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa is set to address the 80 th session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 24. It will be the first time a Syrian president has spoken before the UNGA in nearly six decades. The last Syrian leader to do so was President Nureddin al-Atassi, in 1967—shortly after the dramatic Arab defeat in the Six Day War.

The Assad regime deliberately avoided General Assembly meetings, citing Baathist ideology and insisting that it would not participate until the Arab-Israeli conflict was resolved and Syria had regained the territories that Israel occupied in 1967.

Indeed, starting with Syria’s first president following its independence, Shukri al-Quwatli, the country’s leaders all shunned the UNGA’s annual plenary gatherings. Their absence was more practical than ideological: up until Hafez al-Assad’s rise to power in the 1960s, military coups repeatedly rocked the country and Syria’s leaders were both occupied with internal struggles and fearful that the arrivals might take advantage of their absence from the country in order to seize power themselves.

Finally, some had only brief presidential terms, assuming then losing the presidency before a General Assembly meeting even took place. Others were appointed by coup leaders but had limited constitutional powers or legitimacy.

Al-Sharaa’s speech at the UN summit thus opens a new page for Syria with the world body and the international community more generally. It sends several key message: first and foremost that Syria wants to put the era of dictatorial and military rule behind it, as it transforms from a pariah and a state sponsor of terrorism to a state committed to maintaining international peace and security.

The Syrian leader’s attendance also reflects Damascus’ commitment to eliminating the Assad regime’s chemical weapons program, in cooperation with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons; to wiping out the production and smuggling of illegal drugs, particularly Captagon; and to combating terrorism and preventing its resurgence in Syria. Furthermore, it echoes the country’s adherence to international human rights law, recognition of international committees of enquiry, cooperation with the UN body for Syria’s missing persons, and efforts toward transitional justice.

The visit also represents a significant moment of diplomatic progress for Syria in restoring its international standing, reflected in the presence of the country’s head of state rather than its foreign minister or its permanent mission to the UN. It also serves to encourage the UN to lift international sanctions on Syria, as well as those on President Ahmad al-Sharaa personally.

The visit sends a strong signal that the Syrian state has taken its first steps towards post-war stability, and is proceeding to establish a sustainable system of governance based on constitutional and electoral legitimacy, inclusive of every component of Syrian society, working to strengthen the country’s unity, breaking with the sectarian rule established by the Assad regime, and paving the way for the return of Syrian refugees from neighboring countries and the rest of the world.

These are all demands laid out in the landmark statement of June 30, 2012, by the Action Group for Syria (the Geneva Communiqué), and UN Security Council Resolution 2254 of 2015. Al-Sharaa’s emphasis on them reflects the state’s commitment to a political solution and to the political transition process established by the UN, as well as the confidence Damascus has in the domestic situation and its ability to address outstanding issues, particularly in Suwayda and with the Syrian Democratic Forces in the northeast.

Finally, President al-Sharaa will hold bilateral meetings with fellow heads of state also participating in the General Assembly meetings. This will give them an opportunity to get to know him in person and allowing him to challenge the Israeli narrative about the risks of recognizing the new government in Syria, adding a new layer of international support to the Syrian government, on top of the Arab and Western backing it has received in recent months.